Sleeping under the stars, without the reassurance of the thin tent canvas, it felt like the natural world seeped into our pores just a little more deeply. With just the swaying canopy of an ancient leadwood tree shielding us from a beaming sky of stars, the distant sawing of a leopard in the night was that more thrilling, the sand-papery sounds of large herbivores slurping water below that much more calming. Their earthy scent wafted up to us. And we felt the beautiful, unique privilege of being the only two humans in a very wide stretch of wilderness.

.

But we weren’t completely in the open. We were three metres off the ground, staying the night on Malugwe Platform in the heart of Gonarezhou National Park – one of the very first visitors to the platform since being it was built earlier this year.

Big things are happening in Gonarezhou. In 2017 the Gonarezhou Conservation Trust was formed. The Trust is a comanagement model between Frankfurt Zoological Society and the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority. And since its formation just two years ago, massive strides in the management and development of the park have been taken. Exciting changes where surrounding communities are being given a voice – and a means to benefit from the area, which in turn, benefits the park. Financially, all revenue raised from the park now goes directly back into it. And with a 20-year plan for the park to be self-sustainable, a meticulously designed tourism strategy that focuses on tourism benefiting conservation (and not the other way around) is driving exciting new developments.

Camping the night at Malugwe Platform Gonarezhou National Park

Platform experiences – or as they are to be called “starbeds” – are just a small part of this wider tourism vision, carefully thought out by a dynamic team of people who are getting great things done, and quickly. The platforms are strategically placed in lesser-known areas near pans which are wildlife hotspots in the dry season. Visitors staying here will create a presence in quiet areas, and also get animals used to seeing people. And for people travelling through the park and wanting to appreciate its fantastic scenery and full diversity of habitats, the platforms will be valuable stop off points enroute to the manangas and other campsites. And of course, they create an added revenue stream to the growing bouquet of park accommodation options.

For me, the Malugwe platform could easily be a destination in its own right.

We’d arrived early afternoon – hot, tired, very “hangry” and keen to tuck into our feast of crumbly cheddar and rapidly softening avocado on crackers. Despite a quiet drive in to the pan, we had frightened a lone elephant bull who had swiftly high-tailed when he heard our vehicle. Would all the game be this skittish? The pan seemed eerily quiet and we wondered if we’d just scared away our only game-viewing subject for the afternoon.

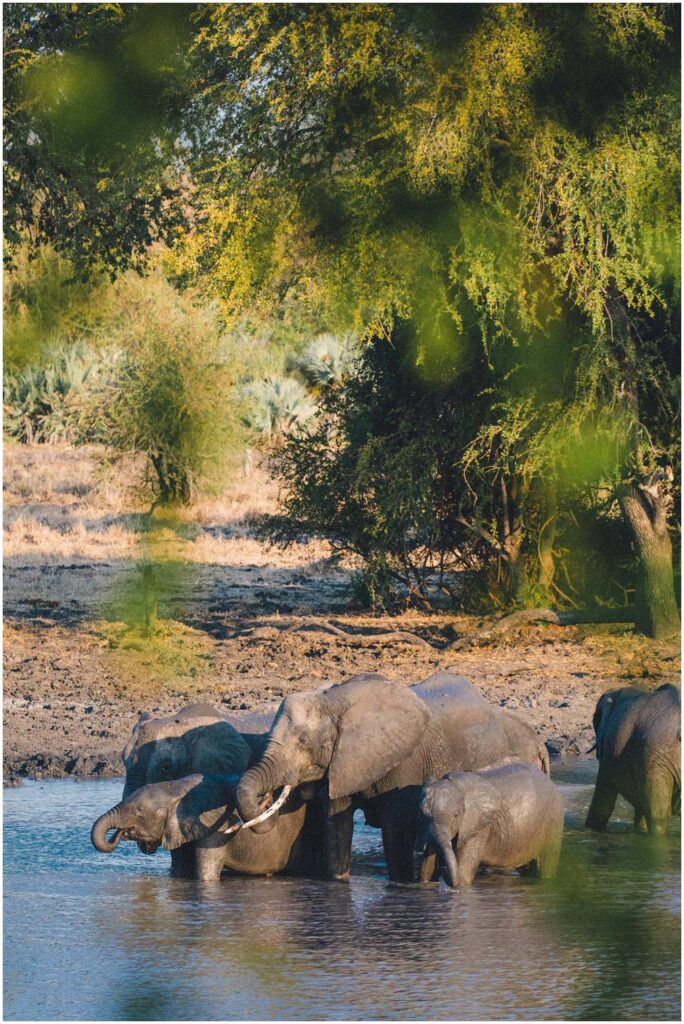

But our fears (and our lunch plans) swiftly evaporated as the first wave of elephants arrived. Scuttling quietly up the platform steps we arrived at the top just as the whole herd emerged from the ilala palm thickets to the northwest of the pan. The matriarch was comfortable and confident, leading her family directly to the water. We dared not move, remembering the young bull we had spooked earlier. But the wind was in our favour and we watched as the twenty-strong herd, oozing delight, drank and played below us for a good forty minutes. Babies played the fool, face-planting into the whatever surface they could face-plant into. Teenagers teased babies, alternately bullying them and mothering them in a riot of happy water snorts and squeals. Eventually, after a low grumble from the matriarch they made a reluctant retreat, departing almost as buoyantly as they had arrived, and leaving the pan once again as still as we had found it on arriving.

.

Babies played the fool, face-planting into the whatever surface they could face-plant into. Teenagers teased babies, alternately bullying them and mothering them in a riot of happy water snorts and squeals.

Tides of elephants and doves

And as if someone had pressed a button, as if on some beaming silent signal, hundreds of cape-turtle doves descended to drink from the pan. Waves of them fluttered down to the muddy water’s edge, their beating wings like a light shower on a tin roof. Both of us grabbed our cameras again, not knowing where to focus, so overwhelming was the avian deluge.

And then the button was pressed again. In one rippling silver wave the doves had vanished. And from nowhere the next elephant herd arrived – the same large numbers – slinking in from the northwest again, grey shadows though the ilala palms. And the same merriment upon approaching water. They drank, played and retreated. The doves returned. A falcon flew over, and the dove-wave rose once more. Then fell. Then a few smaller elephant herds came down and the doves retreated. These patterns continued all afternoon in a busy parade of game-viewing – waves of doves and elephants in and out like the tide. We photographed and filmed solidly for three hours, hunger forgotten, loving the wildlife activity – revelling in the quiet beauty of this little corner of the earth, where we were the only two humans for kilometres around.

“… and what ensued can only be described as a hyena hunt. In the fading light we saw the loping forms of three hyena scuttling between clumps of ilala palms as the elephants fanned out in a trident formation, rushing the thickets to flush the trespassers. “

In between visits by wildlife, the silence was delicious, the views soothing. The fiercely autumnal colours of the spirostachys in the distance were belied by the pastel olives of the nearby ilala palms and the soft blues of a hazy August sky. We took advantage of the quiet moment to get some cheddar on a cracker – foregoing the avocado in favour of haste, but were once again interrupted by a herd of elephant. This time, a small family of five, and this time, not approaching the water with the carefree giddiness we had seen all afternoon.

Had they smelt us? Heard us? Or are they just warier because there are fewer of them? By now the sun had set and the thick grey blanket of dusk was descending. They reached the water’s edge and had just started drinking when one of them screamed a shrill trumpet and hurtled off into an ilala palm thicket – the rest followed and what ensued can only be described as a hyena hunt. In the fading light we saw the loping forms of three hyena scuttling between clumps of ilala palms as the elephants fanned out in a trident formation, rushing the thickets to flush the trespassers. They hunted with furious intent: their heads high, their legs stiff – letting out fearsome growls and charging ilala palms with a righteous ferocity that was both fascinating and terrifying to witness.

“Here at the platform it wasn’t about Gonarezhou’s rugged five-star views and spectacular waterways – it was about slowing down, being mindful of our surroundings – and enjoying that very special and increasingly (terrifyingly) rare commodity – solitude.”

But the hyenas seemed nonplussed. Their pace didn’t change as they loped between safety points, hotly followed by thrashing trunks. The elephantine screams didn’t seem to unsettle them as they unsettled us. After a ferocious game of cat-and-mouse, unseen by their huntresses, the hyenas eventually snuck out of the thicket and began their drink at the exact spot the elephants had just abandoned, managing a few long gulps while the elephants continued their ghost hunt. It was definitely a Rose Rigden moment. The elephants, happy with their patrol work, came swaggering out of the scrub, saw the hyena and swagger changed to murderous charge. Once again the hyenas softly loped off, retreating to the opposite side of the pan where they broke into a few rebellious whoops. The elephants seemed reluctant to declare a truce but thirst won out and they settled down.

Quiet had returned and we became aware of the bubbling chatter of hundreds of double-banded sandgrouse – we must have missed their arrival in the chaos. Their calls, rising in one giant soothing melody – were jaunty, yet calming; their ghostly flutterings below us at the water’s edge indistinct in the thick dusk. We sat quietly in our camp chairs, breathing in the chorus which was so beautifully amplified by the body of water in front of us.

Night fell quickly and we listened as nameless beasts slaked their thirsts. A quick flash of the torch revealed dozens of buffalo, and next to them, the huntress elephant family who had changed location, now peaceful with that slow-blinking slow-drinking contentment of a relaxed pachyderm. A civet crept around the cracking waterline. The water lifted each sound. Out here every drop, gurgle, elephantine wind-break or tummy growl seemed to come from beneath the platform itself. A little while later the hyena began their eerie whoops again, the sound amplified until it seemed to rise in a thrilling crescendo around us.

Silence. Then a shrill trumpet (at the hyena, perhaps?) followed by the happy shuffle and gurge of yet another herd of elephants as they arrived and sank gratefully into the water.

A thin sliver of a quarter moon rose over the pan. We sat mostly in darkness, occasionally checking for new visitors with a quick flash of the torch. There was finally time to eat our crackers – this time we went all out and added two battered tomatoes and a rationed serving of Zimbabwe’s favourite “Crocodile Sauce”. What a feast!

Before getting here I had been nervous to not be sleeping in a tent. Now it felt like the most natural thing in the universe. We both felt deeply calmed by this immersion. Here at the platform it wasn’t about Gonarezhou’s rugged five-star views and spectacular waterways – it was about slowing down, being mindful of our surroundings – and enjoying that very special and increasingly (terrifyingly) rare commodity – solitude.

I lay back in my sleeping bag and studied the outline of the swaying leadwood canopy above me. How long has this tree been here? I tried hard hard to stay awake, to savour the sounds and thrill of this starbed experience but the next thing I knew the white-browed robyn chats were singing their dawn chorus from the undergrowth beneath the platform, the first streaks of purple lighting up the sky. And the first waves of cape-turtle doves were already preparing to descend for the first drink of the day.

For enquiries about accommodation options at Gonarezhou National Park please go their website here – or better still email reservations@gonarezhou.org which is the most direct way of finding out more.

.